Brief History of Western Music (Part 1)

Intended for people who haven't yet learned about this subject.

Western music, meaning the music of most of the European continent, but also its colonies, is unique its development and current form from the music of all the other high cultures of earth: it focuses intensely on polyphony.

Simple polyphony exists to some extend in most cultures, but polyphony as paradigm of music itself is not found anywhere else. This is not to say that Western music is inherently more complex or better than music of other cultures, since indeed middle eastern music is intensely complex in a different way (making use of far more divisions of the octave compared to western music), yet only the Europeans have developed what we now call “chords”, “counterpoint“ and “tonal harmony“.

Music in the ancient world

Let’s begin by looking at how music was made in the ancient world, what kind of music it was, when it was performed, and how it was regarded by scholars. This is an important step, since we in the modern age often forget how radically different our everyday relationship to music is compared to that of our ancestors.

Most importantly, they did not have any recording technology. I really urge you to imagine this, not being able to simply conjur up songs whenever you like. How much of the music you listen to is performed by real people? How much of it is technological playback? Would your daily life include any music at all if this technology wasn’t invented yet? Not only digital, but also analoge recordings too.

The ancients had no radio, record players or smart phones. All music they heard was entirely performed by musicians, or by themselves.

Life was quite a bit more silent, and thus music ironically had more importance. People, compared to our times, sang a lot more. It was common to sing before eating, or after, sing in general at the whim of some feeling or emotion, or when with friends and family. If you are an average wheat farmer, you wouldn’t really hear any music not made by your immediate acquaintances and family unless there was a festival or religious event. It was also not considered as embarrasing to sing in front of others.

This has some interesting effects on society: People know a lot more songs from memory than in our times, since we have no need nor drive to remember them by heart. People compose and sing a lot more spontaneously. Being a good singer is something very valued, and can be compared to being a “living radio” to tie it back to modernity. If someone is a good singer now, sure it might be impressive and you might get recommended to musical colleges, but the average person is not gonna care.

But if you are a good singer in the olden days, people are probably going to even follow you around the village if you begin singing (Unless it’s a larger town with lots of musicians). And since people knew a lot more songs by heart, it was a lot easier to sing in groups together, since everyone was familiar with what they were singing. Today there’s only really a handful songs left that truly everyone knows by heart, like “Happy Birthday” and the national anthem.

Common instruments naturally would be ones that are easy to carry around. Unlike the large pianos or orchestras of later periods, musicians usually were soloists with an accompaniment instrument like a harp, lute, drum, or crotalum (ancient form of castanets). In addition, for larger gatherings of musicians you would have pipes (like the Greek aulos), horns, trumpets, and other instruments that you can only play by using your breath (thus making you unable to sing).

Instrumental music did exist, but it was far outranked by vocal music. The instruments were largely understood as adding extra power to the voices, to highlight them more. Instrumentalists played the melody the singer was singing, they didn’t play “chords”.

Of course, these larger gatherings were either for big festivals or for the local aristrocrat’s court. It was a special occasion, the vast majority of music heard and sung was by soloists.

What were common topics of these songs? This is probably the part that changed the least over time. Songs were often about love, death, thanksgiving, the divine, catastrophe, nature, really anything. Songs would have more mythological and religious elements than our fashion would dictate, but it’s more or less the same.

A look at the Book of Psalms from the bible would confirm this, the range of subjects covers absolutely everything, even self-referencing the production of new music itself in Psalm 96.

This touches on an element that I consider the most prominent difference between current and ancient musical practice: one of the most beloved genres back then was the epic. Modernity knows little to no epics.

An epic is, to put it simply, a very long song in poetic form that retells great events, of heroes or histories of a people, by a bard. Most people probably wouldn’t have the time to remember an entire epic (though this was not' impossible), and they were usually performed with exceeding mastery over the art.

The closest thing I can think of would be either musicals or long TV-shows. They fulfill a very similar role in our culture, especially as objects of reference (Think breaking bad).

People loved these epics, and they are commonly performed at court and in the capitals where the greatest artistic minds dwelled. Epics continued to be made way into the middle ages, but as I will explain later, they began to phase out by that time.

(If you are interested, here is a reconstructed performance of the Iliad, which was supposed to be sung.)

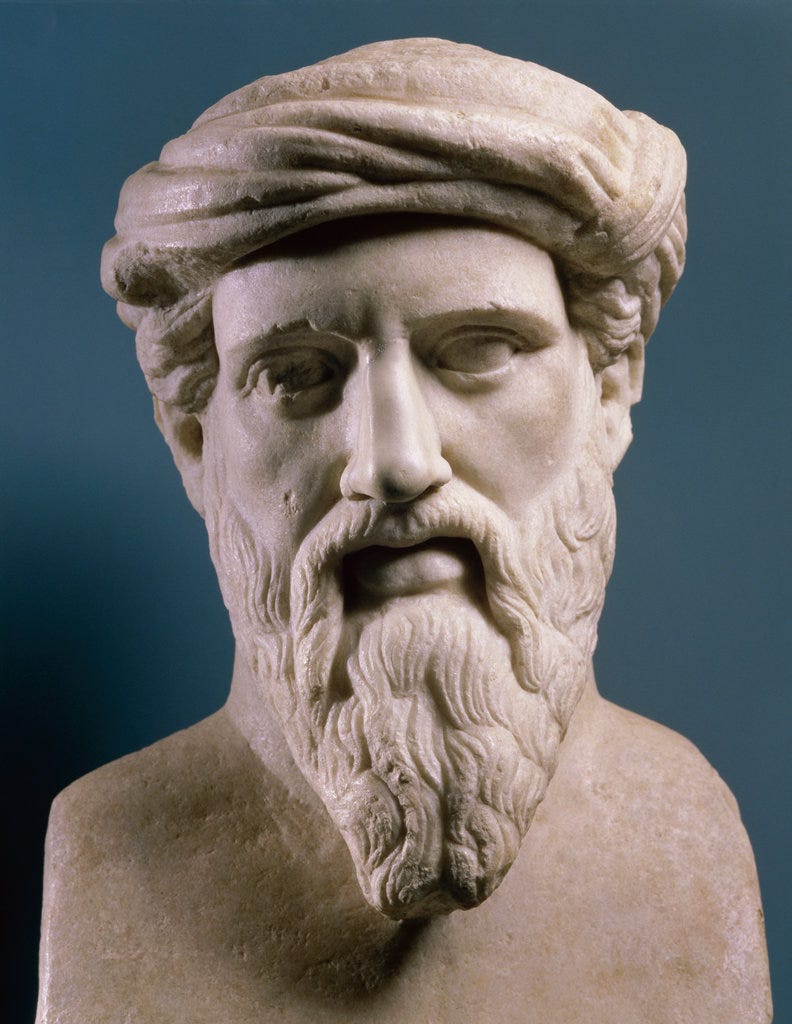

Pythagoras

The first major development that is essential to Western music is the work of Pythagoras. The Greek philosopher and mathmatician has an entire system named after him, and a lot of terms used in music theory have their roots in his achievements. Because of him, the study of music was intimately linked together with the study of mathmatics in medieval quadrivium.

Octave

By using differently sized strings (like those on harps and guitars), Pythagoras realized that striking a string twice as long as a different string produces a note that sounds nearly identical to the other one. This difference roughly matches with the natural voice difference in pitch between men and women, and so was taken as the fundamental core of the entire system. When a man and a woman sing the same song together, even if they don’t realize it, they normally sing it exactly an octave apart. This perfection between the sound and the ratio found in the string lead Pythagoras to link music and mathmatics extensively.

This 2:1 relationship between two pitches is called the octave.

Scale

A scale is a set of notes that fill the space between the octave. That means, beginning from any note, you can sing a variety of different pitches until you reach the next octave above or below your initial point. Pythagoras divided the octave into several different pitches, which are called “notes” of the scale.

They are simply enumerated from one to seven in ascending order, as the eighth one is the next octave, it is counted as “one” again. (There are some more complex alternative divisions such as Pythagora’s twelve-tone divions, but I’ll keep it simple.)

In asia, the scale was most commonly divided into five notes per octave, to illustrate some contrast.

Building on this foundation, more detail was filled in to account for the musical conventions of the Greek practice at the time, with multiple ways to divide the octave into smaller parts, which were categorized into “tetrachords” (collections of four notes, which were stacked), modes (changing the beginning position within a specific scale, thus altering the emphasis of the sound heavily), and more.

The last important term to know is “interval”, which is used to describe the distance between two specific notes. The octave is the most fundamental interval between two notes, having the 2:1 relation. The second most important interval is the “fifth”, which is called so based on its position in the scale starting from the initial note, and is the second most harmonious interval after the octave, with a relation of 3:2.

There are more, but ultimately all someone needs to know is that all pitches are ranked from most pleasant sounding to least pleasant sounding, corresponding to how pure their sound is, since the math and the human experience lines up perfectly. The more simple a geometric shape is, the more pure it visually looks. The same is true of sound

Even to this day, this is felt and hasn’t changed, what has changed is where the line is drawn between “consonant” and “dissonant” (nice sounding and not nice sounding).

Consonant < - > Dissonant:

Octave - Fifth - Fourth - Third - Sixth - Second/Seventh - Tritone

A note or interval being “dissonant” did not mean you weren’t allowed to use it, think of it more like spice. You use less of it and it takes more digression. Tasteful use of it is a skill and valued highly in any age. In the modern era, “prohibition” on excessive dissonance is often regarded as “backwards” or too close-minded, but I would like to point out the culinary parallel to this: We still consider over-salting or using too much pepper to be a bad thing in food. It’s fundamentally the same type of thing, you don’t forbid overdosing pepper because you “hate pepper”, you do it because it ruins the experience or balance of the food.

Naturally, tastes in this way can and have developed. In this regard, I do believe this is like cuisine, where we wouldn’t say Asian food is inherently worse or better than say European food.

Now, another important angle is the intellectual sphere’s view on music in this time period. The Pythagoreans, having already tied music with math, have additionally tied music with astronomy, and thus the cosmos itself. They argued the revolution of the stars and planets, in moving consistent patterns, produce an imperceptable harmonious sound in the heavens. Additionally, Plato and other philosophers attributed moral character to the music, saying they can influence a person’s behavior and mood, and are thus powerful tools that need to be considered carefully.

This means that unlike today, there was no such concept as “personal taste” when it comes to music, at least not as we understand. Music was a serious thing, not something one can flippantly toy with however one likes.

Roman Music

Once the Roman state swept over the mediterranean, they took Greek music and its theory as the basis for their own conception. And unlike with the ancient Greek music, it is easier to find remnants of the late empire’s, in the form of the Roman Chant.

A general rule for all cultures is that the style of music used in the highest spheres of culture, the courts and the temples, influences the music of the general population heavily. Usually, the average sound of the music of a people is extremely similar to the sound of the music of their temples, and religious institutions being inherently more conservative, have a tendency to preserve such music over long periods of time.

Almost all musical developments in the Western world have their origin in musical developments of the Catholic church, rest of culture following suit. This only changed very recently, in the 19th century the roles where reversed.

Now, the Catholic church is not entirely monolithic, some parts of it specifically in Italy and Spain have retained a very close sound to that of the past ages. The Old Roman Chant as it is called forms the basis of the entire middle ages development of music, and thus indirectly the music that came out of the middle ages tradition.

One might notice is sounds quite a bit different to the “Gregorian Chant” that people are more familiar with, it might strike the hearer as more “Eastern” or “Islamic”. This is not incorrect, and in fact much of the music of Mediterranean and the Islamic world has its root in the Greek and Roman form of song, and thus are very similar. Most noticeably, the melodic lines are sung with more slur, having less clear cut off points between individual notes.

This type of music was usually performed by one highly trained chanter, though it was also sung antiphonally with a choir (meaning switching between soloist and choir).

The secular music only really different in that they made far more liberal use of instruments, though Roman pagans most definitely made use of instruments in their worship, the early Christian church almost entirely forbade instruments in the Christian rituals as too distracting.

Music in the Middle Ages

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the musical world of the West was split into many smaller bits, though one musical tradition came to dominate Europe over time. The music sung in Rome, the seat of the papacy, came to define the coming era as the other kingdoms adopted Rome’s conventions.

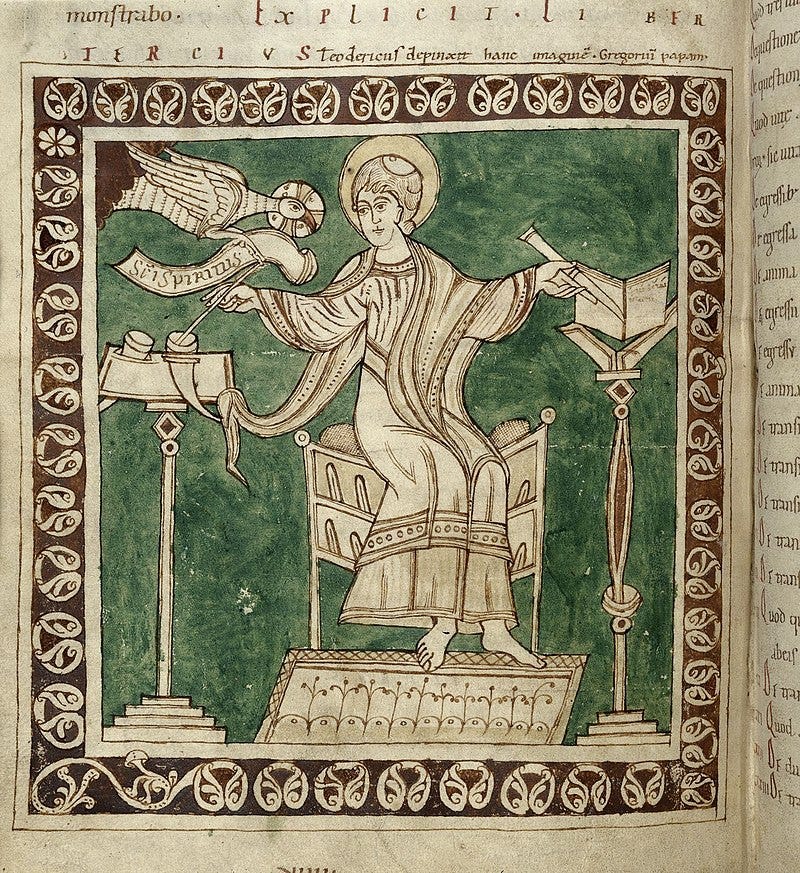

The most important music in the minds of the medievals was doubtlessly the music sung at holy mass, plus the feast days of Christianity. In this time, since organization across many miles was difficult, practices diverged until Charlamagne united much of the tribes in his empire. It was then decided that the compilation of songs from the great Pope Saint Gregory I where to be taken as the gold standard for musical practice. Legends tell of him being directly inspired by the Holy Spirit to write down and notate these songs, for the widespread use in the church across the continent.

These chants have henceforth become known as “Gregorian Chant”, used extensively in the Christian world. They are characterized by being very sober and clear songs, using a lot of Latin poetry methods, and being fairly accessible songs that do not demand virtuosic ability. Great singers often improvised upon these songs, elaborating the melody and heightening key moments in the music.

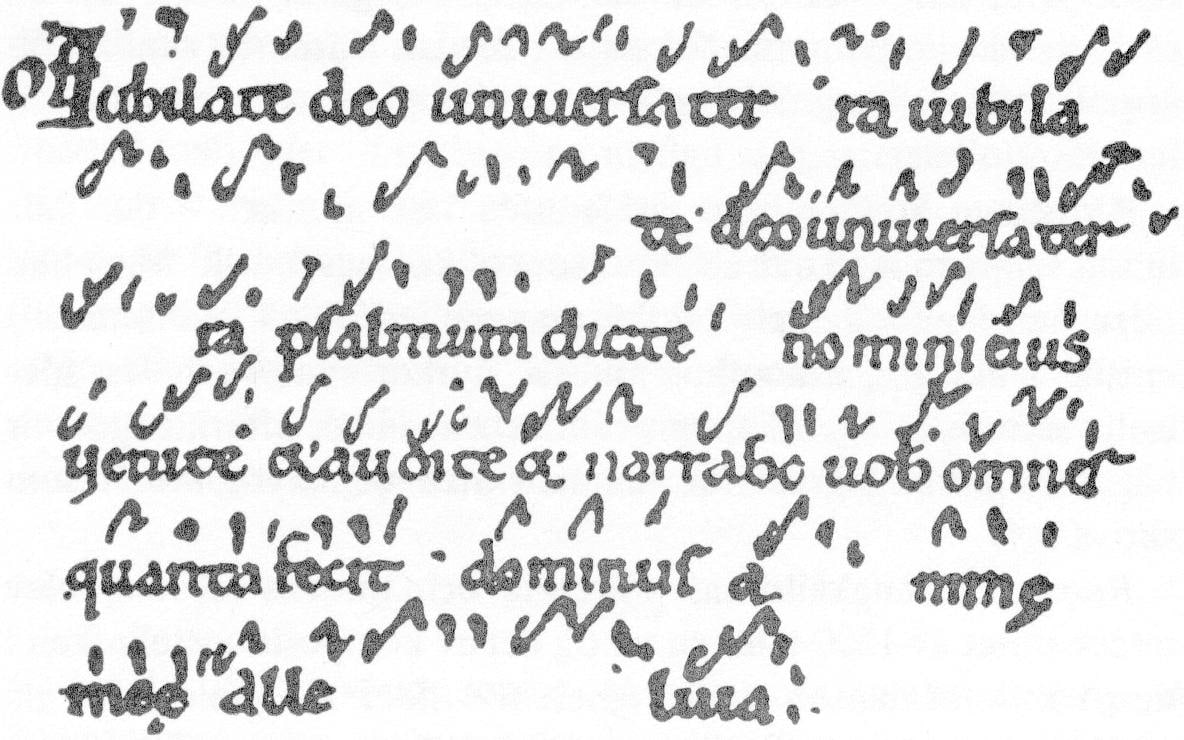

Around the same time, the technology of music notation was undergoing lots of development as well, since it was previously not possible to notate songs propery. Most songs where transmitted directly through hearing, making it difficult to preserve them accurately.

With time, monks came up with a system that tied the pitch of a note to syllables in the text, making it possible to sing new songs you haven’t heard previously. This system is a precursor to our modern notation system, and is called “neumes”, differing in that it didn’t indicate a precise pitch, but a pitch relative to your starting note.

This new invention resulted in songs spreading more easily, and the preservation of older songs was likewise less of a challenge. Beginning in monasteries, new practices in chanting these melodies emerged, the early polyphony. The point of such techniques was to increase volume and power in the sung parts of the mass, since they did not have accompaniment of any kind during this time.

Organum

This early polyphony (meaning multiple voices) was simple, consisting of only a few rules, and is called “organum”. The simplest two types of organum are the organum based on the fifth, and the organum based on the forth, where the choir transposed the melody either exactly by a fifth, or with some elaboration, by the forth. One part of the choir sung the melody unaltered, while another part of the choir sung the melody with the changed pitch.

Here are some listening examples, the one I made presents first the melody by itself, then the melody with added fifth-organum, and then again but with forth-organum.

Notice how in the forth-organum, the two distinct voices begin and end on the same note.

These two videos present nice examples of fifth and forth organum respectively.

These examples are accurate, but might be somewhat academic and dry. For a more soulful and artistic performance I recommend Farya Faraji’s rendition of a famous medieval hymn, also making use of organum:

The expansion of the harmonic vocabulary of these musicians paved the way for Europe’s intricate polyphony.

The next trick they utilized was holding the same note like a drone under the melody, resulting in colorful intervals to appear naturally above.

Since these techniques were improvised for the most part, it started becoming more complex once written out. The cathedrals, especially in larger cities, became quite comfortable with displaying more and more musical innovation, especially in medieval France.

New Styles

Léonin is one of the most influential composers from this era, living in the 12th century. Most of the works from this time are anonymous, and Pérotin is one of the very few artists who we are explicitely told about.

His style is unique compared to older organum for having different rhythms for the two singing voices. Instead of them always moving in tandem, with different pitches, they can now move independetly, also with different pitches.

Usually, he would take a common chant melody, stretch it in length, and use it as a bassline for the second higher voice. The second voice was quite elaborate and ornate from time to time, whereas the “cantus firmus” (fixed melody) of the bottom voice was more structually set in stone, like bedrock for a building.

After Léonin came the similarly named composer Pérotin, again working in Paris. He was part of the next generation after Léonin, and so lived from the 12th to the early 13th century, he based much of his work on the revered Léonin.

Though he was a lot more daring than his predecessor, making use not only of two independent voices, but twice that amount. With four independent melodies sung by a choir, he composed for the glorious Notre-Dame cathedral liturgy. He was so well recieved that we now still know not only his name, but also as with Léonin, have his scores for performance.

Similarly to Léonin, there still was a bottom voice (Cantus Firmus) that never falters from the given chant melody and text, though it is stretched to incredible lengths in this above piece. The other melodies surrounding it pass through another, and sometimes go below that forth voice in pitch. The rhythm is mostly based on 3/4 time, meaning the notes are organized into units of three instead of four, resulting in a dance-like quality.

This 3/4 time was much prefered in the middle ages because of the reference to the Holy Trinity, with 4/4 time (what we know as common time) being sligthly rarer, but still used.

There is some debate as to whether instruments where used in these performances during this time, which is not something we can make a definitive statement on. What we do know is that acapella was the prefered method in either case.

The pipe organ did exist, though was likely not yet used much in the churches, it was far smaller and more popular for street performances and festivals.

This concludes the first part of the history, next time I will talk about the Notre-Dame school and the Renaissance, where we finally get the first instances of exclusively instrumental music and triadic harmony.